NOTE: The Growth Economics Blog has moved sites. Click here to find this post at the new site.

One of my continuing questions about research in economic growth is why it insists on remaining so focused on manufacturing to the exclusion of the other 70-95% of economic activity in most economies.

I’ll pick on two particular papers here, mainly because they are widely known. The first is Chad Syverson’s “What Determines Productivity?“, a survey piece that reviews the literature on firm-level productivity measurement. The main theme of the survey is that productivity varies widely across firms. Which firms? Syverson cites his own work showing that within disaggregated manufacturing industries, productivity varies by a factor or roughly 2-to-1 between the 90th and 10th percentiles. The rest of the survey contains citation after citation of papers studying manufacturing sector productivity differences.

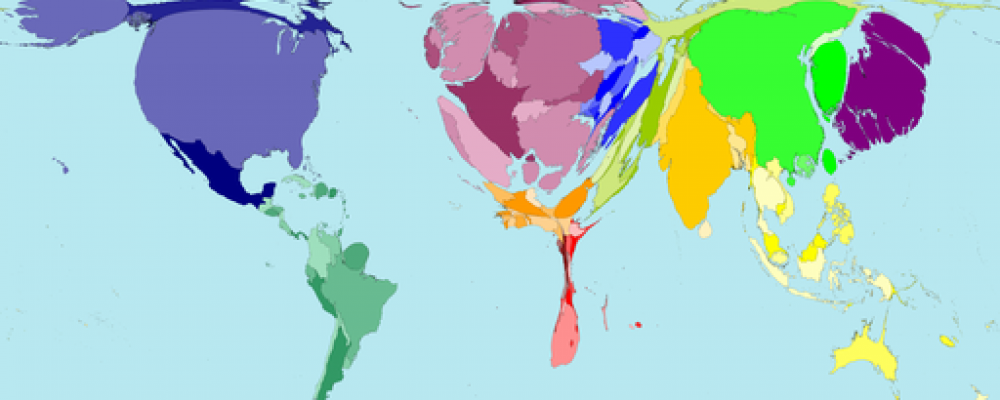

Hsieh and Klenow, in their paper looking at the aggregate impacts of these kinds of productivity gaps, look at manufacturing plants in India, China, and the U.S. They find that the productivity differences, if eliminated, would raise manufacturing productivity by 40-50% in China and India. What goes unsaid in Hsieh and Klenow is that a 40-50% increase in productivity in manufacturing would be something like a 10% increase in aggregate GDP in India, and a 15% increase in China. Both still impressive numbers, but much smaller than the headline result because the manufacturing sector is *not* the dominant source of value-added for any country.

Why do we persist in focusing on this particular subset of industries, sectors, and firms? I think one of the main reasons is that our data collection is skewed towards manufacturing, and we end up with a “lamppost” problem. We look for our lost keys underneath the lamppost because that’s where the light is, even though the keys are out in the dark somewhere.

Our system of classifying economic activity is part of the problem. It was designed to track manufacturing originally, and then other sectors were sort of stapled on as an afterthought. To see what I mean, consider the main means of classifying value-added by sector (ISIC codes) and the main means of classifying occupations (ISCO codes).

ISIC stands for International Standard Industrial Classification. It was designed to distinguish one goods-producing industry from another, not to provide any nuance with respect to services. The original ISIC system had 10 industries, and 2 of them were manufacturing. Those 2 manufacturing industries were divided into 20 total sub-industries. *All* of the other economic activity in the economy was assigned a total of 25 sub-categories. So we’ve got “manufacture of wood and cork, except for furniture” and “manufacture of rubber products” under manufacturing in general. But we’ve got “wholesale and retail trade” as a sub-category under commerce.

From ISIC’s perspective, separately tracking the manufacture of wood of cork products (but not furniture, that’s different) was important, but it was sufficient to just lump all wholesale and retail activity in the economy together. Even in 1960, all manufacturing value-added in the U.S. was only slightly larger than all wholesale and retail trade value-added. But the former is subdivided into 20 sub-categories, while the latter is simply a sub-category of its own. Our methods of categorizing value-added are a relic of an economy now 60-70 years old, and even back then this was un-related to the relative importance of different sectors.

And no, ISIC has not kept up with the times. Yes, the current ISIC revision 4 now breaks out wholesale and retail trade into its own sub-categories (2-digit) and sub-sub-categories (3-digit). Wholesale and retail trade now has 20 3-digit categories. Retail sale of automotive fuel, for example. Manufacturing has 71 3-digit categories. Manufacture of irradiation, electromedical, and electrotherapeutic equipment, for example.

In the current ISIC version, “Education” is a top-level sector, similar to “Manufacturing”. But while manufacturing still has 24 sub-sectors at the 2-digit level, and 71 at the 3-digit, education has 1 sub-sector at the 2-digit level, and 5 at the 3-digit level. “Human health and social work” is a top-level sector, and it has 3 2-digit sub-sectors, and 9 3-digit sub-sectors. We have “hospital activities” and “medical and dental practice activities” as 2 of the 9, so you can at least separate out your optometrist appointment from your emergency appendectomy.

Think of how ridiculous this is. We are careful to distinguish that your dining room table was produced by a different sub-sector than the one the produced the wooden salad bowl you use on that table. But we do not bother to distinguish my last tooth cleaning from my grandma’s last orthopedic appointment.

The calcification of our view of the sources of economic activity continues if we look at occupation codes. These are from ISCO, and the last revision to the codes was in 2008. ISCO uses a similar multi-digit system as ISIC. The one-digit code of 2 means “Professionals”, and below that is the two-digit code of 25, for “Information and communications technology professionals”. That two-digit code has the following lower-level breakdown:

- 251 Software and applications developers and analysts

- 2511 Systems analysts

- 2512 Software developers

- 2513 Web and multimedia developers

- 2514 Applications programmers

- 2519 Software and applications developers and analysts not elsewhere classified

- 252 Database and network professionals

- 2521 Database designers and administrators

- 2522 Systems administrators

- 2523 Computer network professionals

- 2529 Database and network professionals not elsewhere classified

These are incredibly high level designations in the tech world. Imagine that you are building a new web site for your retail business, and you need someone to do user interface. Do you ask for someone who does “web and multimedia development”, or someone who does “software development”? No. Those are far too general. You’d post an ad for someone who does UI/UX design, with a knowledge of html, css, and perhaps javascript. You might also require them to know Photoshop. And this person is completely different than the person you’d hire to build your iPhone app, who needs to know Xcode at a minimum, and is different from the guy who builds the Android app.

On the other hand, we have the one-digit code of 7 that means “Craft and related trade workers”. Below that is code 71, for “Building and related trades workers, excluding electricians”. That category is broken down further as follows:

- 711 Building frame and related trades workers

- 7111 House builders

- 7112 Bricklayers and related workers

- 7113 Stonemasons, stone cutters, splitters and carvers

- 7114 Concrete placers, concrete finishers and related workers

- 7115 Carpenters and joiners

- 7119 Building frame and related trades workers not elsewhere classified

- 712 Building finishers and related trades workers

- 7121 Roofers

- 7122 Floor layers and tile setters

- 7123 Plasterers

- 7124 Insulation workers

- 7125 Glaziers

- 7126 Plumbers and pipe fitters

- 7127 Air conditioning and refrigeration mechanics

- 713 Painters, building structure cleaners and related trades workers

- 7131 Painters and related workers

- 7132 Spray painters and varnishers

- 7133 Building structure cleaners

The separate occupations involved in building a house are pretty clearly delineated here: framers, plumbers, painters, etc.. Heck, ISCO makes sure to distinguish “spray painters” from regular old “painters”, and those are all different from people who clean building structures (I’m guessing these people have power washers?).

While all the individual occupations of building are house are broken down, all the individual occupations of building a successful web-site are lumped into one, maybe two occupations? “Software developers” is not the same level of disaggregation as “plumbers”, despite ISCO having them both coded to a 4-digit level.

If you go back to the ISIC codes, you can get an idea of how our conception of economic activity atrophied somewhere around 1960. What follows are some current descriptions of 3-digit sectors from ISIC.

This is for the “Manufacture of Furniture”:

This division includes the manufacture of furniture and related products of any material except stone, concrete and ceramic. The processes used in the manufacture of furniture are standard methods of forming materials and assembling components, including cutting, moulding and laminating. The design of the article, for both aesthetic and functional qualities, is an important aspect of the production process.

Some of the processes used in furniture manufacturing are similar to processes that are used in other segments of manufacturing. For example, cutting and assembly occurs in the production of wood trusses that are classified in division 16 (Manufacture of wood and wood products). However, the multiple processes distinguish wood furniture manufacturing from wood product manufacturing. Similarly, metal furniture manufacturing uses techniques that are also employed in the manufacturing of roll-formed products classified in division 25 (Manufacture of fabricated metal products). The molding process for plastics furniture is similar to the molding of other plastics products. However, the manufacture of plastics furniture tends to be a specialized activity.

Note the detailed differences accounted for in the definition of furniture manufacture. ISIC is careful to distinguish that wood furniture is distinct from just processing wood, because of some aesthetic element. And yes, the techniques for metal and plastic furniture are similar to other 3-digit industries, but there is something particular about furniture that sets it apart from these.

Now here’s the description of the “Computer Programming, Consultancy, and Related Activities” code:

This division includes the following activities of providing expertise in the field of information technologies: writing, modifying, testing and supporting software; planning and designing computer systems that integrate computer hardware, software and communication technologies; on-site management and operation of clients’ computer systems and/or data processing facilities; and other professional and technical computer-related activities.

On the other hand, anyone who does anything even remotely connected with IT gets lumped into one gigantic category. Write code in Ruby on Rails for web sites? Convert legacy systems at a major corporation from COBOL over to C? Do tech support for a bank? Manage a server farm? Create mobile apps in Xcode? All that shit’s basically the same, right? Computer stuff.

This concentrated focus on manufacturing is problematic because it means we cannot undertake detailed studies similar to Syverson’s or Hsieh and Klenow’s about the sectors that are actually growing rapidly. Is there a lot of productivity dispersion in software? How about in retail, or home health care? These industries actually account for large and growing shares of economic activity, so productivity losses in them are relatively important compared to manufacturing.

The classification system also helps sustain the myth that this sector is somehow inherently more valuable than other types of economic activity. It plays into this idea that a country is failing if its manufacturing sector is declining as a share of GDP. But that decline in manufacturing is simply evidence that we have gotten very, very adept at it, and that there is an upper limit on the marginal utility of having more manufactured goods. All that effort that goes into tracking individual types of manufacturing activity would be far better spent tracking more service-sector sub-categories and occupations, because those are actually going to expand in size in the future.

And yes, I just wrote 2000 words about ISIC and ISCO codes. What has happened to me?

Great entry, I love it. You bring really good examples and raise awareness of a topic I wasn’t even aware of (although I’ve started doing research using industry data).

Part of the problem is the failure of Congress to provide the data collection agencies the funds or budgets they need to expand the industry detail of the data they collect. Since 1980 real budgets for data collection have contracted almost every year and the various data collection agencies have been hard pressed to even continue doing what they were already doing, let alone improve the process. So for the most part the system remains essentially what it was in 1980.

Most government activities have people that need or use the activity so they have effective lobbies for Congress to fund those activities. But data collection has virtually no one lobbying Congress for more data. Interestingly, in the early 1980s the National Association of Business Economics actually voted to not lobby for larger data collection budgets because they though they should make their contribution to the Reagan administrations plans to cut the size of government.

Great point, and i don’t know enough about the politics of that to say much. But I think this is a general problem – occasionally social scientists will make a big enough stink that Census will keep/add questions. We need a little agitation from economists to get better statistics.

Super interesting post. I’m glad you wrote it!

In general, there seems to be a tradeoff whenever you try to construct a taxonomy of the economy.

One the one hand, to make your categories most useful, you want them equally populated/detailed. This entails basing your classification scheme on the economy of the present day. However, the weakness of this approach is that when things change (i.e., the digital revolution and the trend toward more services), your classification scheme falls behind and loses power.

To counter this downside, you might want a classification scheme based on theoretical principles (i.e., industries based on matter vs energy vs information) that works for all economies over all tims. But then you end up with the opposite problem, where some of your categories are far more important and detailed than others.

Overall, it seems to be a problem with no perfect solution. Even a fast update period has downsides like the lack of continuity and comparability over time.

I think you are spot on. Sometimes I wonder if we should just track GDP for goods separately, and have a different measure for services. And not worry about them adding up or being comparable so much.

Some countries have almost no manufacturing at all and are poor with little employment. Import substitution is a simple way forward for them by increase of manufacturing as long as they are good enough and cheap enough to compete with the imports without increasing the domestic price. Volume is a consideration in viability too. So they obsess on these sort of data. It gives them a clue where they need to focus.

I don’t see much point in importing exporting raw or basically produced copper and then re-importing it as copper wire. Or basic foodstuffs either which need some basic manufacturing processes.

In developed economies then the obsession is less critical because of all the other areas of employment but in undeveloped countries they should be obsessed, manic, really.

Sorry, delete first occurrence of importing.

Pingback: Le marché du travail des femmes (6) – les professions (2) |

Pingback: Berensztein | What drives productivity growth?

Pingback: Why Information Industrial Classification Diversity Grows | The Growth Economics Blog