NOTE: The Growth Economics Blog has moved sites. Click here to find this post at the new site.

The projected future path of labor productivity in the U.S. is perhaps the most important input to the projected future path of GDP in the U.S. There are lots of estimates floating around, many of them pessimistic in the sense that they project labor productivity growth to be relatively slow (say 1.5-1.8% per year) over the next few decades compared to the relatively fast rates (roughly 3% per year) seen from 1995-2005. Robert Gordon has laid out the case for low labor productivity growth in the future. John Fernald has documented that this slowdown probably pre-dates the Great Recession, and reflects a loss of steam in the IT revolution starting in about 2007. This has made Brad DeLong sad, which seems like the appropriate response to slowing productivity growth.

An apparent alternative to that pessimism was published recently by Byrne, Oliner, and Sichel. Their paper is titled “Is the IT Revolution Over?”, and their answer is “No”. They suggest that continued innovation in semi-conductors could make possible another IT boom, and boost labor productivity growth in the near future above the pessimistic Gordon/Fernald rate of 1.5-1.8%.

I don’t think their results, though, are as optimistic as they want them to be. A different way of saying this is: you have to work really hard to make yourself optimistic about labor productivity growth going forward. In their baseline estimate, they end up with labor productivity growth of 1.8%, which is slightly higher than the observed rate of 1.56% per year from 2004-2012. To get themselves to their optimistic prediction of 2.47% growth in labor productivity, they have to make the following assumptions:

- Total factor productivity (TFP) growth in non-IT producing non-farm businesses is 0.62% per year, which is roughly twice their baseline estimate of 0.34% per year, and ten times the observed rate from 2004-2012 of 0.06%.

- TFP growth in IT-producing industries is 0.46% per year, slightly higher than their baseline estimate of 0.38% per year, and not quite double the observed rate from 2004-2012 of 0.28%

- Capital deepening (which is just fancy econo-talk for “build more capital”) adds 1.34% per year to labor productivity growth, which is one-third higher than their baseline rate of 1.03% and, and double the observed rate from 2004-2012 of 0.74%

The only reason their optimistic scenario doesn’t get them back to a full 3% growth in labor productivity is because they don’t make any optimistic assumptions about labor force quality/participation growth.

Why these optimistic assumptions in particular? For the IT-producing industries, the authors get their optimistic growth rate of 0.46% per year by assuming that prices for IT goods (e.g. semi-conductors and software) fall at the fastest pace observed in the past. The implication of very dramatic price declines is that productivity in these sectors must be rising very quickly. So essentially, assume that IT industries have productivity growth as fast as in the 1995-2005 period. For the non-IT industries, they assume that faster IT productivity growth will raise non-IT productivity growth to it’s upper bound in the data, 0.62%. Why? No explanation is given. Last, the more rapid pace of productivity growth in IT and non-IT will induce faster capital accumulation, meaning that its rate rises to 1.34% per year. This last point is one that comes out of a simple Solow-type model of growth. A shock to productivity will temporarily increase capital accumulation.

In the end here is what we’ve got: they estimate labor productivity will grow very fast if they assume labor productivity will grow very fast. Section IV of their paper gives more detail on the semi-conductor industry and the compilation of the price indices for that industry. Their narrative explains that we could well be under-estimating how fast semi-conductor prices are falling, and thus under-estimating how fast productivity in that industry is rising. Perhaps, but this doesn’t necessarily imply that the rest of the IT industry is going to experience rapid productivity growth, and it certainly doesn’t necessarily imply that non-IT industries are going to benefit.

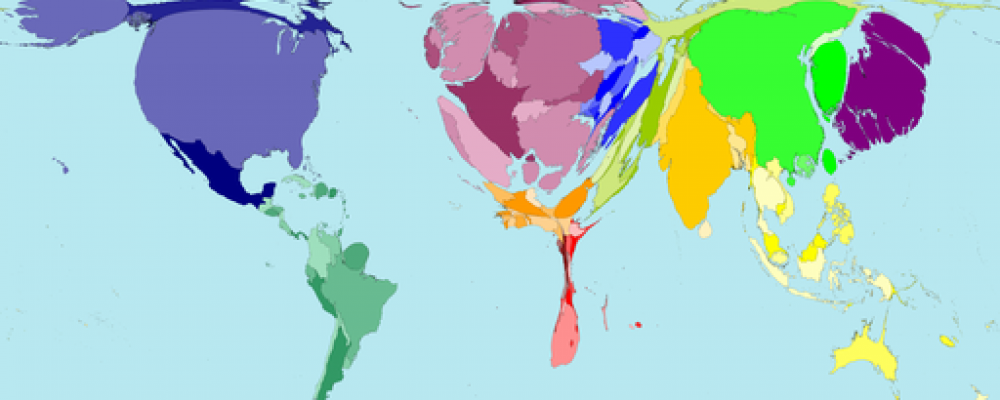

Further, even rapid growth in productivity in the semi-conductor industry is unlikely to create any serious boost to US productivity growth, because the semi-conductor industry has a shrinking share of output in the U.S. over time. The above figure is from their paper. The software we run is a booming industry in the U.S., but the chips running that software are not, and this is probably in large part due to the fact that those chips are made primarily in other countries. If you want to make an optimistic case for IT-led productivity growth in the U.S., you need to make a software argument, not a hardware argument.

I appreciate that Byrne, Oliner, and Sichel want to provide an optimistic case for higher productivity growth. But that case is just a guess, and despite the fact that they can lay some numbers out to come up with a firm answer doesn’t make it less of a guess. Put it this way, I could write a nearly exact duplicate of their paper which makes the case that expected labor productivity growth is only something like 0.4% per year simply by using all of the lower bound estimates they have.

Ultimately, there is nothing about recent trends in labor productivity growth that can make you seriously optimistic about future labor productivity growth. But that doesn’t mean optimism is completely wrong. That’s simply the cost of trying to do forecasting using existing data. You can always identify structural breaks in a time series after the fact (e.g. look at labor productivity growth in 1995), but you cannot ever predict a structural break in a time series out of sample. Maybe tomorrow someone will invent cheap-o solar power, and we’ll look back ten years from now in wonder at the incredible decade of labor productivity growth we had. But I can’t possibly look at the existing time series on labor productivity growth and get any information on whether that will happen or not. Like it or not, extrapolating current trends gives us a pessimistic growth rate of labor productivity. Being optimistic means believing in a structural break in those trends, but there’s no data that can make you believe.

Pingback: Links for 9-24-14 | The Penn Ave Post

Relax if you can. Productivity is simply constrained by effective demand at the moment and has been constrained by it much of the time from 2004 to 2012. When labor share rises or there is another contraction, effective demand space will open up and productivity will rise…

You can go to my blog and do a search on productivity. You will see posts with graphs of productivity stalling against the effective demand limit through decades of business cycles.

effectivedemand.typepad.com

I am optimistic about productivity potential. Yet the obstacle is raising labor’s share back up. I am not so optimistic that will happen.

I think this a subject that really calls for a “no one knows what they are talking about” moment. For some reason (or more likely combination of reasons) productivity from 1946-1973 appears to have gone up at a roughly 3% per year. Then for some reason(s), much speculated about but poorly supported by evidence, it fell to around 1.5% per year from 1973-1995. Then in 1995 it jumped up again (and the jump was a big surprise) to between 2.5% and 3% until roughly 2007. It now appears to have fallen back to 1.8% per year, with speculations as to the reason why (Cowen and Gordon believe technical innovation has slowed although they don’t try to explain why). My own speculations, and young economists looking to make names for themselves on research papers take note, is demographics bulges and contractions (Depression/War II kids born from 1929 to 1945 was a smaller population coming into the work force in the 1950s and 60s (with the large draft based military taking about 3,000,000 workers out of the population every year till the end of draft and Vietnam War which was 1973), while boomers and women exploded into the work force in the 1970s and 80s. Again, productivity went up again with another demographic of low birth rate population (Generation X) started coming of age in the 1990s. Also worker population shifts from low to higher productivity activities – in the 1950s and 60s, for instance, from working in cotton fields to working in steel mills and auto plants and such) and from those plants to service industries and back office work in the 1990s – may account for some of it. Also, the rise and fall and rise and fall again of government and private R&D and basic science research spending may effect the rate of technical innovation and resulting productivity booms. But I don’t know, this may all be correlation, and not a drop of causation. Folks out there, please start your research!

The changes in productivity that you point out are all explained my changes in effective demand. For example, in the late 90’s, productivity was able to increase because labor share was rising and capacity utilization was falling. Labor was then able to increase its consumption potential in more labor hours and income potential, which allowed increased productivity to increase production with demand limits. The late 90’s was an unusual moment but perfectly understandable.

Pingback: Best of the Web: 14-09-24, nr 1073 | Best of the Web

But how much of pessimism about the numerator of private output per capita is due to slack demand, fewer new technologies being put in use, discouraged workers dropping out of the labor force, governments not investing in productive projects because of deficit fears, etc., and how much is due to technological slow down? The distinction is important as in principle it is easier to fix slack demand than technological growth.

Like it. Also Gabriele Oettingen has a nice study about optimism&pesimism, the most effective planners use a balance of optimism and pessimism.

Nice. I’ll take a look. I think that optimism, and dare I say naivety, are part of the package that supports cooperative equilibria.