NOTE: The Growth Economics Blog has moved sites. Click here to find this post at the new site.

I just finished reading “The Long Process of Development” by Jerry Hough and Robin Grier. The quick response is that you should read this book. If that’s enough, then go get it. All the rest of this post is just some of my reactions to the book.

The basic idea of HG is to trace out how long it took England and Spain (and by extension, their colonies Mexico and the U.S.) to evolve the elements of “good institutions” that we think promote economic growth. Clearly the process went faster in some of these places than others, but the point is that it took centuries regardless of who we are talking about.

HG look at the development of an effective state in England through history. For them, England gets a minimally effective state with Henry VII in 1485. His victory in the War of the Roses (and in particular his ruthless elimination of others with claims to the throne) gave him a government that had at least some control over the entire area of England and Wales. So is that when England has good institutions? No, not really. From that point, it is another two hundred and four years until the Glorious Revolution and what we might call the beginnings of constitutional monarchy. All good? Not quite. It is another one hundred and forty three years before the Reform Act of 1832 generates the barest seeds of what might be called inclusive institutions. Even if you think that England in 1832 had “good institutions” for economic development, that was three hundred and forty-seven years after England got a functioning central government. If we lower our sights and say that the Glorious Revolution had given England the “good institutions” necessary for economic development, then that was still two hundred years after England got a functioning central government.

The second major example used by HG is Spain. By 1504, Isabella had acquired a kingdom that essentially looks like modern Spain in geographic reach. She was the monarch of Castile, the Moors had been forced out of Granada, and she had brought Aragon into the kingdom by marrying Ferdinand. HG then document that despite this geographic reach, the government of Spain was not an effective central government in the way that Henry VII or VIII had over England. Even Philip II’s reign in the late 1500’s did not consolidate government in a way that seems consistent with his numerous foreign military activities. HG argue that Spain was about 200 years behind England, and only reached an effective central government around 1700. It would be arguably another 280 years after that before Spain got what we would call “good institutions”.

Regardless of the exact historical case study, HG’s point is that developing modern institutions the support sustained economic growth takes centuries, even in one case – England – where all the breaks kept going their way.

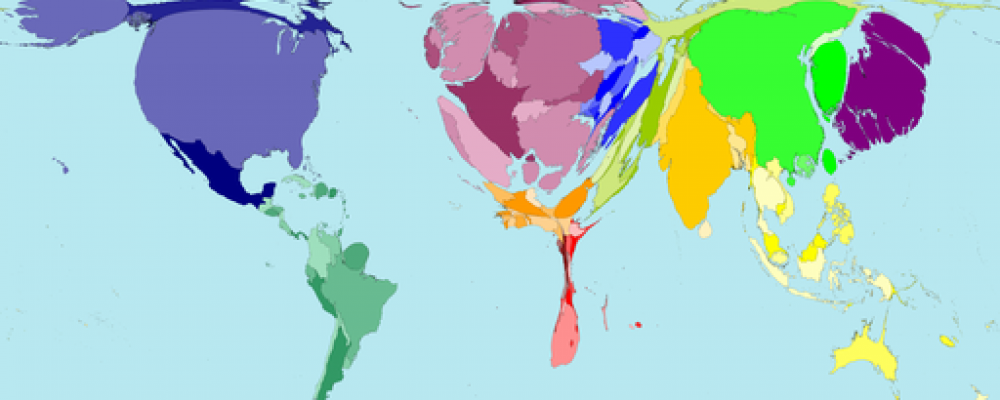

What is the point of this regarding development and growth? HG suggest that a large number of developing countries have a central government with the capabilities roughly equal to those of Henry VII. Many of them began as separately defined states only in the 1960’s, and in the subsequent fifty years have perhaps gained the ability to extend their powers of taxation and coercion to all corners of their geographic area. In places like Afghanistan, they cannot even do that.

Asking, expecting, or advising these countries to adopt “good institutions” is to ask them to skip between two and five centuries of institutional evolution in one leap. Developing countries evolving their own stable institutional structures that support economic growth is going to be long, ugly, and likely violent – just like it was in every single currently rich country. HG’s work says that institutions are not just another technology. While you can play catch-up relatively easily with technology (e.g. adopting mobile phones without landline networks), you cannot do the same with institutions.

Further, institutional development is always going to involve some coercion. Some group is going to have to be dragged kicking and screaming into the new institutional arrangement. HG clearly reject the idea that new social contracts will spontaneously get re-negotiated as circumstances change, as in the old North and Weingast interpretation of the Glorious Revolution in England. In contrast they accept the more Mancur Olson-ian view, that social contracts are whatever the dude with the gun says they are. The only way to accelerate the development process is to accelerate the concentration of coercive power with one group/party/coalition. From that perspective, the problem with the U.S. attempts at state building in Afghanistan and Iraq was not that they intervened, but that this intervention was half-assed and ended before the job was done. If you are going to intervene, pick a winner and then make sure they win. Trying to equalize power across different factions is precisely the wrong thing you should do to encourage institutional development. That is me spinning the argument out to a logical extreme, but it makes the point.

A last mild critique of HG is that it has a fault similar to most other work on institutions. It does not define what a “good institutions” are. We know that England and the U.S. have them now, and that Spain seems to have them at least since after Franco. We know that England had “good” institutions in or around the 1800’s, and Spain apparently didn’t. And we know that England and Spain had “bad” institutions before the 1500’s. So it must be that institutional evolution takes somewhere between three and five centuries? But what precisely is it that England and Spain have today that they didn’t in 1500? What is a good institution?

HG are more clear than many on this point. They consciously limit themselves to examining whether a central government has effective control of taxation and violence within its borders. But of course, what does effective control mean? What does taxation mean – what’s the difference between a tribute, a donation, expropriation, and a tax? Does control of violence simply mean that all the people coercing others wear the same uniform?

This critique doesn’t eliminate the value of reading the book. The general point about the long time lags in the evolution of institutions (good or bad) is excellent. It is hard to fight time compression when reading history, and HG make clear that the institutions literature needs to get far more serious about that fight.