NOTE: The Growth Economics Blog has moved sites. Click here to find this post at the new site.

A few papers of interest regarding the persistent effect of historical conditions (geographic or not) on subsequent development:

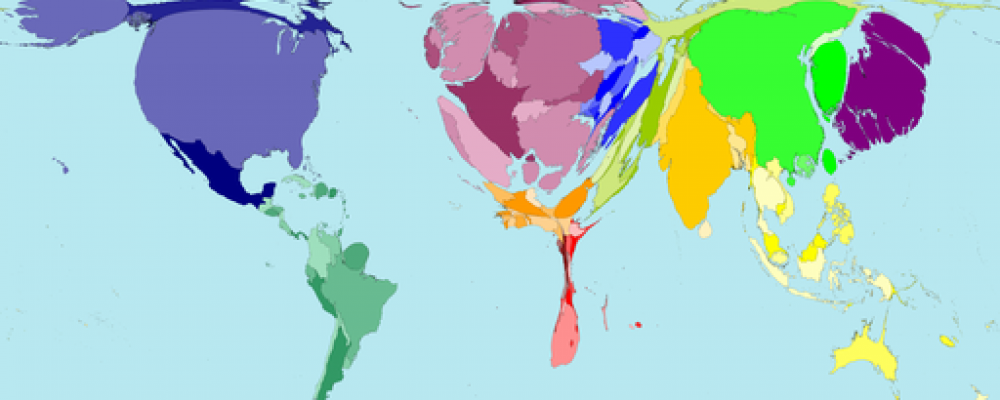

- Marcella Aslan’s paper on the TseTse fly and African development is now out in the American Economic Review. I believe I’ve mentioned this paper before, so go read it finally. Develops an index of suitability for TseTse flies by geography, then shows that within Africa higher TseTse suitability is historically associated with less intensive agriculture, fewer domesticated animals, lower population density, less plow usage, and more slavery (If you are queasy about using Murdock’s ethnographic atlas, then avoid this paper). Marcella shows that TseTse suitability is currently related to lower light intensity (everyone’s favorite small-scale measure of development), *but* this effect disappears if you control for historical state centralization. The idea is that the TseTse prevented the required density from forming to create proto-states, and that these places remain underdeveloped. Great placebo test in this paper – she can map the TseTse suitability index of the whole world, and show that it has no relationship to outcomes. The TseTse is a uniquely African effect, and she is not picking up general geographic features.

- James Ang has a working paper out on the agricultural transition and adoption of technology. Simple idea is to test whether the length of time from when a country hit the agricultural transition is related to their level of technology adoption in 1000 BCE, 1 CE, or 1500 CE (think “did they use iron?” or “did they use plows?”). Short answer is that yes, it is related. Places that experienced ag. transition sooner had more technology at each year. Empirically, he uses instruments for agricultural transition that include distance to the “core” areas of transition (China, Mesopotamia, etc..) and indexes of biological endowments of domesticable species (a la Jared Diamond, and operationalized by Olsson and Hibbs). The real question for this kind of research is the measure of technology adoption. We (meaning Comin, Easterly, and Gong) retrospectively code places as having access to technologies in different years. A worry is that because some places are currently poor (for non-agricultural reasons) the world never bothered to adopt their particular technologies, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they were technologically unsophisticated for their time.

- Dincecco, Fenske, and Onorato have a paper out on historical conflict and state development. The really interesting aspect here is how Africa differs from other areas of the world. Across the world and over history (meaning from 1400 to 1799) wars are associated with greater state capacity today. That is, places that were involved in conflicts in the past are now stronger states (measured as their ability to tax) than those without conflict. The basic theory is that wars allow states to concentrate their power. However, historical conflict is unrelated to current civil conflicts…except in Africa. In Africa, historical wars are correlated with current civil conflicts, and this is associated with poor economic outcomes today, so things are bad on multiple fronts. Here’s my immediate, ill-informed, off-the-cuff analysis: In non-African places, wars generated strong states who were able to use their power to completely and utterly eliminate ethnic groups or cultural groups that were alternative power centers. They don’t have armed civil conflicts today because the cultural groups that might have agitated conflict were wiped out or so completely assimilated that they don’t exist any more. In Africa, central states were just not as successful in eliminating competing cultural groups, so they remain viable sources of conflict. Africa’s problem, perhaps, was a lack of conclusive wars in the past.